Instructor's Notes

LearningCurve activities on nouns and pronouns, and prepositions and conjunctions, are available at the end of the Review of Sentence Structure section of this handbook.

R2 Basic Sentence Elements

This section reviews the parts of speech and the types of clauses and phrases.

R2-

There are ten parts of speech: nouns, pronouns, adjectives, adverbs, verbs, prepositions, conjunctions, articles, demonstratives, and interjections.

Nouns Nouns function in sentences or clauses as subjects, objects, and subject complements. They also serve as objects of various kinds of phrases and as appositives. They can be proper (Burger King, Bartlett pear, Rachael Ray, Trader Joe’s) or common (tomato, food, lunch, café, waffle, gluttony). Common nouns can be abstract (hunger, satiation, indulgence, appetite) or concrete (spareribs, soup, radish, champagne, gravy). Nouns can be singular (biscuit) or plural (biscuits); they may also be collective (food). They can be marked to show possession (gourmet’s choice, lambs’ kidneys). Nouns take determiners (that lobster, those clams), quantifiers (many hotcakes, several sausages), and articles (a milk shake, the eggnog). They can be modified by adjectives (fried chicken), adjective phrases (chicken in a basket), and adjective clauses (chicken that is finger-

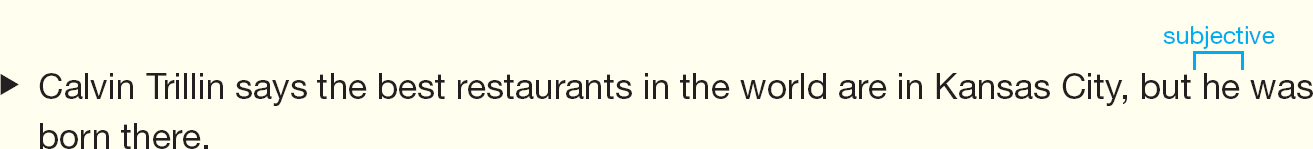

Pronouns Pronouns come in many forms and have a variety of functions in clauses and phrases.

Personal pronouns function as replacements for nouns and come in three case forms:

Subjective, for use as subjects or subject complements: I, we, you, he, she, it, they.

Objective, for use as objects of verbs and prepositions: me, us, you, him, her, it, them.

Possessive: mine, ours, yours, his, hers, theirs. Possessive pronouns also have a determiner form for use before nouns: my, our, your, his, her, its, their.

![]()

Personal pronouns also come in three persons (first person: I, me, we, us; second person: you; third person: he, him, she, her, it, they, them), three genders (masculine: he, him; feminine: she, her; neuter: it), and two numbers (singular: I, me, you, he, him, she, her, it; plural: we, us, you, they, them).

Reflexive pronouns, like personal pronouns, function as replacements for nouns, nearly always replacing nouns or personal pronouns in the same clause. Reflexive pronouns include myself, ourselves, yourself, yourselves, himself, herself, oneself, itself, themselves.

![]()

Reflexive pronouns may also be used for emphasis.

![]()

Indefinite pronouns do not refer to a specific person or object: each, all, everyone, everybody, everything, everywhere, both, some, someone, somebody, something, somewhere, any, anyone, anybody, anything, anywhere, either, neither, none, nobody, many, few, much, most, several, enough.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Relative pronouns introduce adjective (or relative) clauses. They come in three forms: personal, to refer to people (who, whom, whose, whoever, whomever), nonpersonal (which, whose, whichever, whatever), and general (that).

![]()

![]()

![]()

Interrogative pronouns have the same forms as relative pronouns but have different functions. They serve to introduce questions.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Demonstrative pronouns are pronouns used to point out particular persons or things: this, that, these, those.

![]()

![]()

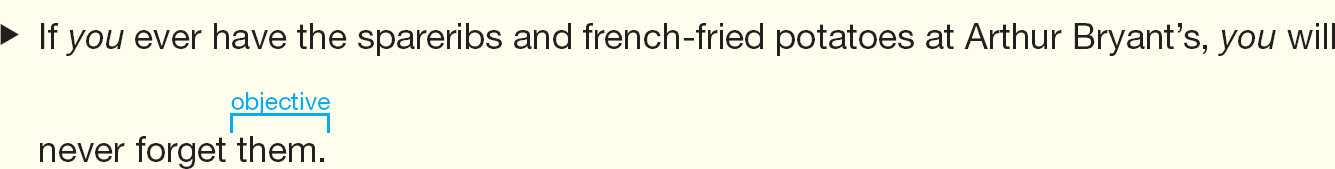

Adjectives Adjectives modify nouns and pronouns, and they usually appear immediately before or after nouns they modify. As subject complements (sometimes called predicate adjectives), they may be separated by the verb from nouns or pronouns they modify.

![]()

![]()

Some adjectives change form in comparisons.

![]()

![]()

Some words can be used as both pronouns and adjectives; nouns are also sometimes used as adjectives.

![]()

(See also G7-b.)

Adverbs Adverbs modify verbs (eat well), adjectives (very big appetite), and other adverbs (extremely well done). They often tell when, how, where, why, and how often:

![]()

![]()

![]()

Like adjectives, adverbs can change form for comparison.

![]()

A number of adverbs are formed by adding -ly to an adjective (hearty appetite, eat heartily). With adverbs that end in -ly, the words more and most are used when making comparisons.

![]()

The conjunctive adverb is a special kind of adverb used to connect the ideas in two sentences or independent clauses. Familiar connectives include consequently, however, therefore, similarly, besides, and nevertheless.

![]()

Finally, adverbs may evaluate or qualify the information in a sentence.

![]()

(See also G7-a.)

Verbs Verbs tell what is happening in a sentence by expressing action (cook, stir) or a state of being (be, stay). Depending on the structure of the sentence, a verb can be transitive (Jerry bakes cookies) or intransitive (Jerry bakes for a living); an intransitive verb that is followed by a subject complement (Jerry is a fine baker, and his cookies always taste heavenly) is often called a linking verb.

Nearly all verbs have several forms (or principal parts), many of which may be irregular rather than follow a standard pattern. In addition, verbs have various forms to indicate tense (time of action or state of being), voice (performer of action), and mood (statement, command, or possibility). Studies have shown that because verbs can take so many forms, the most common errors in writing involve verbs. (See also G5.)

Verb phrases. Verbs divide into two primary groups: (1) main (lexical) verbs and (2) auxiliary (helping) verbs that combine with main verbs to create verb phrases. The three primary auxiliary verbs are do, be, and have, in all their forms.

do: does, did, doing, done

be: am, is, are, was, were, being, been

have: has, had, having

These primary auxiliary verbs can also act as main verbs in sentences. Other common auxiliary verbs (can, could, may, might, shall, should, will, would, must, ought to, used to), however, cannot be the main verb in a sentence but are used in combination with main verbs in verb phrases. The auxiliary verb works with the main verb to indicate tense, mood, and voice.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Principal parts of verbs. All main verbs (as well as the primary auxiliary verbs do, be, and have) have five forms. The forms of a large number of verbs are regular, but many verbs have irregular forms.

| Form | Regular | Irregular |

| Infinitive or base | sip | drink |

| Third- |

sips | drinks |

| Past | sipped | drank |

| Present participle (-ing form) | sipping | drinking |

| Past participle (-ed form) | sipped | drunk |

The past and past participle for most verbs in English are formed by simply adding -d or -ed ( posed, walked, pretended, unveiled). However, a number of verbs have irregular forms, most of which are different for the past and the past participle.

For regular verbs, the past and past participle forms are the same: sipped. All new verbs coming into English have regular forms: format, formats, formatted, formatting.

Irregular verbs have unpredictable forms. Their -s and -ing forms are generally predictable, just like those of regular verbs, but their past and past participle forms are not. In particular, be careful to use the correct past participle form of irregular verbs.

Listed here are the principal parts of fifty-

| Base | Past Tense | Past Participle |

| be: am, is, are | was, were | been |

| beat | beat | beaten |

| begin | began | begun |

| bite | bit | bitten |

| blow | blew | blown |

| break | broke | broken |

| bring | brought | brought |

| burst | burst | burst |

| choose | chose | chosen |

| come | came | come |

| cut | cut | cut |

| deal | dealt | dealt |

| do | did | done |

| draw | drew | drawn |

| drink | drank | drunk |

| drive | drove | driven |

| eat | ate | eaten |

| fall | fell | fallen |

| fly | flew | flown |

| freeze | froze | frozen |

| Base | Past Tense | Past Participle |

| get | got | got (gotten) |

| give | gave | given |

| go | went | gone |

| grow | grew | grown |

| have | had | had |

| know | knew | known |

| lay | laid | laid |

| lead | led | led |

| lie | lay | lain |

| lose | lost | lost |

| ride | rode | ridden |

| ring | rang | rung |

| rise | rose | risen |

| run | ran | run |

| say | said | said |

| see | saw | seen |

| set | set | set |

| shake | shook | shaken |

| sink | sank | sunk |

| sit | sat | sat |

| speak | spoke | spoken |

| spring | sprang (sprung) | sprung |

| steal | stole | stolen |

| stink | stank | stunk |

| swear | swore | sworn |

| swim | swam | swum |

| take | took | taken |

| teach | taught | taught |

| tear | tore | torn |

| throw | threw | thrown |

| wear | wore | worn |

| win | won | won |

| write | wrote | written |

Tense. As writers, even native speakers may find it difficult to put together sentences that express time clearly through verbs: Time has to be expressed consistently from sentence to sentence, and shifts in time perspective must be managed smoothly. In addition, certain conventions permit time to be expressed in unusual ways: History can be written in present time to dramatize events, or characters in novels may be presented as though their actions are in present time. The following examples of verb tense provide only a partial demonstration of the complex system indicating time in English.

Present. There are three basic types of present time: timeless, limited, and instantaneous. Timeless present-

![]()

Limited present-

![]()

Instantaneous present-

![]()

Present-

![]()

Past. There are several kinds of past time. Some actions must be identified as having taken place at a particular time in the past.

![]()

In the present perfect tense, actions may be expressed as having taken place at no definite time in the past or as occurring in the past and continuing into the present.

![]()

![]()

Action can even be expressed as having been completed in the past prior to some other past action or event (the past perfect tense).

![]()

Future. The English verb system offers writers several different ways of expressing future time. Future action can be indicated with the modal auxiliary will.

![]()

A completed future action can even be viewed from some time farther in the future (future perfect tense).

![]()

Continuing future actions can be expressed with will be and the -ing form of the verb.

![]()

The right combination of verbs with about can express an action in the near future.

![]()

Future arrangements, commands, or possibilities can be expressed.

![]()

![]()

![]()

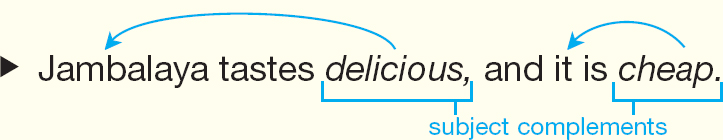

Voice. A verb is in the active voice when it expresses an action taken by the subject. A verb is said to be in the passive voice when it expresses something that happens to the subject.

In sentences with active verbs, it is apparent who is performing the action expressed in the verb.

![]()

In sentences with passive verbs, it may not be clear who is performing the action.

![]()

The writer could reveal the performer by adding a phrase (by the chef), but the revision would also create a clumsy sentence. Graceful, clear writing relies on active, rather than passive, verbs. Passive forms do fulfill certain purposes, however, such as expressing the state of something.

![]()

![]()

Passives can give prominence to certain information by shifting it to the end of the sentence.

![]()

Writers also use passives to make sentences more readable by shifting long noun clauses to the end.

Mood. Mood refers to the writer’s attitude toward a statement. There are three moods: indicative, imperative, and subjunctive. Most statements or questions are in the indicative mood.

![]()

![]()

Commands or directions are given in the imperative mood.

![]()

The subjunctive mood is used mainly to indicate hypothetical, impossible, or unlikely conditions.

![]()

![]()

Prepositions Prepositions occur in phrases, followed by objects. (The uses of prepositional phrases are explained in R2-c.) Most prepositions are single words (at, on, by, with, of, for, in, under, over, by), but some consist of two or three words (away from, on account of, in front of, because of, in comparison with, by means of ). They are used to indicate relations — usually of place, time, cause, purpose, or means — between their objects and some other word in the sentence.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Objects of prepositions can be single or compound nouns or pronouns in the objective case (as in the preceding examples), or phrases or clauses acting as nouns.

![]()

![]()

Conjunctions Like prepositions, conjunctions show relations between sentence elements. There are coordinating, subordinating, and correlative conjunctions.

Coordinating conjunctions (and, but, for, nor, or, so, or yet) join logically comparable sentence elements.

![]()

![]()

Subordinating conjunctions (although, because, since, though, as though, as soon as, rather than) introduce dependent clauses.

![]()

![]()

Correlative conjunctions come in pairs, with the first element anticipating the second (both . . . and, either . . . or, neither . . . nor, not only . . . but also).

![]()

Articles There are only three articles in English: the, a, and an. The is used for definite reference to something specific; a and an are used for indefinite reference to something less specific. The Mexican restaurant in Westbury is different from a Mexican restaurant in Westbury. (See T1.)

Demonstratives This, that, these, and those are demonstratives. Sometimes called demonstrative adjectives, they are used to point to something specific.

![]()

![]()

Interjections Interjections indicate strong feeling or an attempt to command attention: phew, shhh, damn, oh, yea, yikes, ouch, boo.

R2-

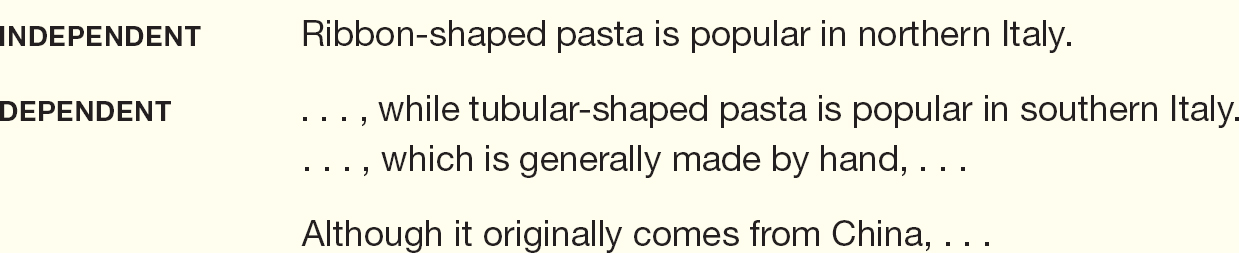

Like independent clauses, all dependent clauses have a subject and a predicate. Unlike independent clauses, however, dependent clauses cannot stand by themselves as complete sentences; they always occur with independent clauses as part of either the subject or the predicate.

There are three types of dependent clauses: adjective, adverb, and noun.

Adjective clauses Also known as relative clauses, adjective clauses modify nouns and pronouns in independent clauses. They are introduced by relative pronouns (who, whom, which, that, whose) or adverbs (where, when), and most often they immediately follow the noun or pronoun they modify. Adjective clauses can be either restrictive (essential to defining the noun or pronoun they modify) or nonrestrictive (not essential to understanding the noun or pronoun); nonrestrictive clauses are set off by commas, and restrictive clauses are not (see P1-c and P2-b).

![]()

![]()

![]()

Adverb clauses Introduced by subordinating conjunctions (such as although, because, and since), adverb clauses nearly always modify verbs in independent clauses, although they may occasionally modify other elements (except nouns). Adverb clauses are used to indicate a great variety of logical relations with their independent clauses: time, place, condition, concession, reason, cause, circumstance, purpose, result, and so on. They are generally set off by commas.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Noun clauses Like nouns, noun clauses can function as subjects, objects, or complements (or predicate nominatives) in independent clauses. They are thus essential to the structure of the independent clause in which they occur and so, like restrictive adjective clauses, are not set off by commas. A noun clause usually begins with a relative pronoun, but the introductory word may sometimes be omitted.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

R2-

Like dependent clauses, phrases can function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs in sentences. However, unlike clauses, phrases do not contain both a subject and a verb. (A phrase, of course, cannot stand on its own but occurs as part of an independent clause.) The six most common types of grammatical phrases are prepositional, appositive, participial, gerund, infinitive, and absolute.

Prepositional phrases Prepositional phrases always begin with a preposition and function as either an adjective or an adverb.

![]()

![]()

Appositive phrases Appositive phrases identify or give more information about a noun or pronoun just preceding. They take several forms. A single noun may also serve as an appositive.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Participial phrases Participles are verb forms used to indicate certain tenses (present: sipping; past: sipped). They can also be used as verbals — words derived from verbs — and function as adjectives.

![]()

A participial phrase is an adjective phrase made up of a participle and any complements or modifiers it might have. Like participles, participial phrases modify nouns and pronouns in sentences.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Gerund phrases Like a participle, a gerund is a verbal. Ending in -ing, it even looks like a present participle, but it functions as a noun, filling any noun slot in a clause. Gerund phrases include complements and any modifiers of the gerund.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Infinitive phrases Like participles and gerunds, infinitives are verbals. The infinitive is the base form of the verb, preceded by to: to simmer, to broil, to fry. Infinitives and infinitive phrases function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Absolute phrases The absolute phrase does not modify or replace any particular part of a clause; it modifies the whole clause. An absolute phrase includes a noun or pronoun and often includes a past or present participle as well as modifiers. Nearly all modern prose writers rely on absolute phrases. Some style historians consider them a hallmark of modern prose.

![]()

![]()