Chapter Introduction

What Causes Emotional and Motivated Behavior?

RESEARCH FOCUS 12-

BEHAVIOR FOR BRAIN MAINTENANCE

NEURAL CIRCUITS AND BEHAVIOR

OLFACTION

GUSTATION

EVOLUTIONARY INFLUENCES ON BEHAVIOR

ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES ON BEHAVIOR

INFERRING PURPOSE IN BEHAVIOR: TO KNOW A FLY

REGULATORY AND NONREGULATORY BEHAVIOR

REGULATORY FUNCTION OF THE HYPOTHALAMIC CIRCUIT

ORGANIZING FUNCTION OF THE LIMBIC CIRCUIT

EXECUTIVE FUNCTION OF THE FRONTAL LOBES

CLINICAL FOCUS 12-

STIMULATING AND EXPRESSING EMOTION

AMYGDALA AND EMOTIONAL BEHAVIOR

PREFRONTAL CORTEX AND EMOTIONAL BEHAVIOR

EMOTIONAL DISORDERS

CLINICAL FOCUS 12-

CONTROLLING EATING

CLINICAL FOCUS 12-

EXPERIMENT 12-

CONTROLLING DRINKING

CONTROLLING SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

CLINICAL FOCUS 12-

SEXUAL ORIENTATION, SEXUAL IDENTITY, AND BRAIN ORGANIZATION

COGNITIVE INFLUENCES ON SEXUAL BEHAVIOR

12-1

The Pain of Rejection

We use words like sorrow, grief, and heartbreak to describe a loss. Loss evokes painful feelings, and the loss or absence of contact that comes with social rejection leads to hurt feelings. Several investigators have attempted to discover whether physically painful and emotionally hurtful feelings are manifested in the same neural regions.

Physical pain (say, hot or cold stimuli) is easy to inflict, but inducing equivalently severe emotional, or affective, pain is more difficult. Ethan Kross and colleagues (2011) performed an experiment that may have succeeded in balancing participants’ degree of emotional and physical pain.

Using fMRI, they scanned 40 people who had recently gone through an unwanted breakup. To compare brain activation, the participants viewed two photographs: one of their ex-

Emotional cue phrases associated with each photograph directed the participants to focus on a specific experience they shared with each person. The physical stimulus employed by the researchers, which was administered in a separate session, was either painfully hot or painless warm stimulation of participants’ forearm.

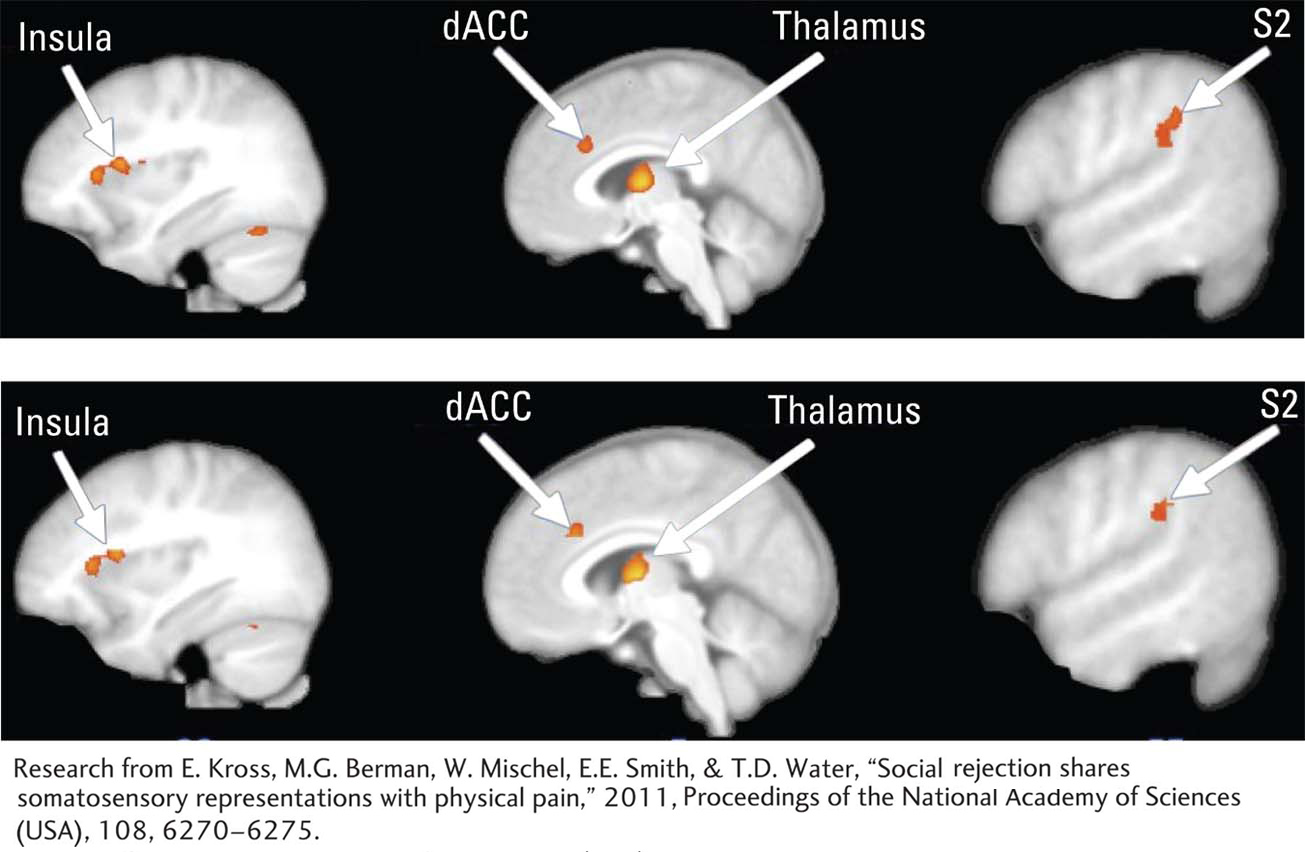

The research question is, do physical pain and social pain have a common neuroanatomical basis? The results, shown in the illustration, reveal that four regions respond to both types of pain: the insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), somatosensory thalamus, and secondary somatosensory cortex (S2). The conclusion: Social rejection hurts in much the same way physical pain hurts.

Previous studies, including Eisenberger and colleagues, 2003, 2006, showed anterior cingulate activity during the experience of both physical and emotional pain. But new results also showed activity in cortical somatosensory regions related to physical pain. The results imaged by Kross and colleagues suggest that the brain systems underlying emotional reactions to social rejection may have developed by co-

Another insight from the Kross study is that normalizing the activity of these brain regions probably provides a basis for both physical and mental restorative processes. Seeing the similarity in brain activation during social pain and physical pain helps us understand why social support can reduce physical pain, much as it soothes emotional pain.

These fMRIs result from averaging scans from 40 participants to image the brain’s response to physical or emotional pain. We see activation in the insula, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), somatosensory thalamus, and/or secondary somatosensory cortex (S2).

Knowing that the brain makes emotional experience real—

This chapter begins by exploring the causes of behavior. Sensory stimulation, neural circuits, hormones, and reward are primary factors in behavior. We focus both on emotion and on the underlying reasons for motivation—behavior that seems purposeful and goal-

Research on the neuroanatomy responsible for emotional and motivated behavior focuses on a neural circuit formed by the hypothalamus, the limbic system, and the frontal lobes. But behavior is influenced as much by the interaction of our social and natural environments and by evolution as it is by biology. To explain how all these interactions affect the brain’s control of behavior, we concentrate on two specific examples, feeding and sexual activity. Our exploration leads us to revisit the idea of reward, which is key to explaining emotional and motivated behaviors.