A Guided Writing Assignment: ARGUMENT

A Guided Writing Assignment*

ARGUMENT

The following guide will lead you through the process of writing an argument essay. Although the assignment focuses on argument, you will probably need to use one or more other patterns of development in order to argue effectively for your position.

YOUR ESSAY ASSIGNMENT

Take a position on a controversial issue and write an argument that makes a narrowly focused arguable claim; offers logical supporting reasons and evidence that readers will find convincing; appeals to readers’ needs and values; and takes alternative viewpoints into consideration. You may choose an issue that interests you or your readers or select one from the list below:

- buying American-made products,

- racial quotas in college admissions policies,

- paying college athletes,

- providing a free college education to prisoners,

- donating kidneys to save the lives of others,

- an environmental problem or issue in your community, and

- mandatory drug testing for high school extracurricular activities.

|

||||||||||||||||

|

1 Choose and narrow a controversial issue. To check whether an issue is controversial, try the following.

The issues listed in the assignment, and most of the issues you are likely to come up with initially, are very broad. Try one or more of these strategies to narrow the issue you have chosen.

Then consider whether you can explore your topic fully in a brief essay. If not, try another narrowing strategy. |

|||||||||||||||

2 Consider your purpose, audience, and point of view. Use idea-generating strategies appropriate to your learning style to generate evidence and appeals that will be most effective given your readers. For example, verbal learners may wish to freewrite, pragmatic learners may wish to create lists or columns, social learners may wish to discuss these issues with classmates. Purpose: What do you want to happen as a result of your argument? . . . change readers’ minds? . . . make readers more certain of their beliefs? . . . inspire readers to take a specific action? Audience: Who are your readers, and how best can you tailor your argument to them? Ask yourself questions like these:

Point of view: What point of view is most appropriate to your position and purpose and to your relationship with your readers?

|

||||||||||||||||

3 Explore your issue. To come to a more nuanced understanding, explore your issue thoroughly before taking a position.

Use the ideas you come up with when drafting your argument. |

||||||||||||||||

4 Research your issue.

Then take notes on the most relevant sources to use when drafting your argument. (Hint: Sources can not only provide evidence to support your position; they can also provide background information and deepen your insight into a range of viewpoints.) Note: To avoid accidental plagiarism, be sure to enclose quotations in quotation marks and use your own words and sentences when summarizing and paraphrasing information from sources. Also record all publication details you will need to cite your sources (author, title, publisher and site, publication date, page numbers, and so on). |

||||||||||||||||

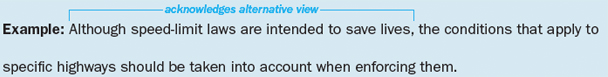

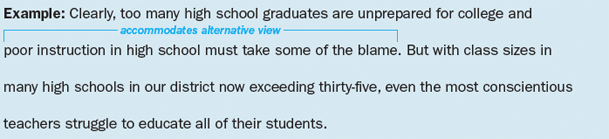

5 Consider alternative viewpoints. Drawing on your research, brainstorm reasons those holding alternative positions would be likely to offer. Choose the reasons your readers are likely to find most persuasive, and then decide whether you should acknowledge, accommodate, or refute those reasons.

Doing so shows that you take the view seriously but that you think your claim outweighs it.

give a counterexample (an exception to the opposing view), question the opponent’s facts by presenting alternative facts or statistics or an alternative interpretation, question the credibility of “experts,” question outdated examples, facts, or statistics, present the full context of statistics or quotations, and point to any examples of faulty or fallacious reasoning, such as examples that are not representative (sweeping generalization) or conclusions based on too little evidence (hasty generalization). (For more on fallacious reasoning, see Chapter 20.) Collaboration. In small groups, take turns offering examples that show how each member plans to acknowledge, accommodate, or refute opposing views; critique those strategies; and suggest more effective approaches. Then work independently to list opposing viewpoints for your own argument and develop strategies for dealing with the opposition. |

||||||||||||||||

|

6 Draft your thesis statement. Be sure your thesis . . . makes an arguable claim,

is specific enough to explore fully, and

avoids absolutes.

Here is an example of a thesis that is arguable, specific, and appropriately limited: Example: Although the carelessness of merchants and electronic tampering contribute to the problem, U.S. consumers are largely to blame for the recent increase in credit card fraud. |

|||||||||||||||

7 Choose a line of reasoning and a method of organization. Choose a line of reasoning that best suits your audience.

Here are four common ways to organize an argument

Method 1 works best with agreeing audiences, methods 2 and 3 with neutral or wavering audiences, and method 4 with disagreeing audiences. Also decide how to arrange your reasons and evidence as well as the alternative views you canvass: From strongest to weakest? Most to least obvious? Most to least familiar? Draw graphic organizers or make outlines to try out each alternative. (Outlines may work best for verbal and rational learners, graphic organizers—for spatial learners, but using techniques that challenge you can be helpful, too.) |

||||||||||||||||

8 Draft your argument essay. Use the following guidelines to keep your essay on track.

|

||||||||||||||||

|

9 Evaluate your draft and revise as necessary. Use Figure 21.4, “Flowchart for Revising an Argument Essay”, to evaluate and revise your draft. |

|||||||||||||||

|

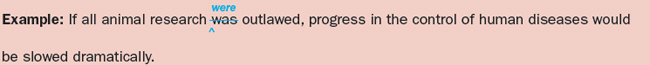

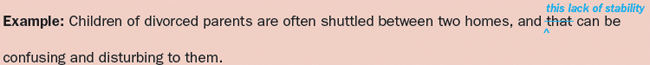

10 Edit and proofread your essay. Refer to Chapter 10 for help with...

Watch out particularly for ambiguous pronouns and problems with the subjunctive mood.

|

|||||||||||||||