14.9 Change of Variables Using JacobiansPrinted Page 962

We often find a single integral, ∫baf(x)dx using the method of substitution. To use substitution, we let x=g(u). Then dx=g′(u)du, and ∫baf(x)dx=∫dcf(g(u))g′(u)du

where a=g(c) and b=g(d). In making this substitution, the variable x is replaced by g(u), and the factor g′(u) is introduced into the integrand.

Sometimes it is easier to find a double integral, ∬ by changing the variables x and y to the polar coordinates r and \theta, by letting x=r\cos \theta, y=r\sin \theta, and d\!A=r\,dr\,d\theta. Then \begin{equation*} \iint\limits_{R}f(x,y)\,d\!A=\iint\limits_{R^{\#}}f(r\cos \theta ,r\sin \theta) r\,dr\,d\theta \end{equation*}

where R^{\#} is the region R expressed in polar coordinates. In changing the variables from rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates, the factor r is introduced into the integrand on the right.

When finding a triple integral \iiint\limits_{E}f(x, y, z)\,{dV}, we discussed two types of change of variables: Sometimes the variables x, y, and z were changed to cylindrical coordinates; other times the variables were changed to spherical coordinates.

963

Using cylindrical coordinates (r,\theta,z), we get \iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE}f(x,y,z)\,{\it dV}=\iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE^{\#}}f(r\cos \theta ,r\sin \theta ,z)~r\,dr\,d\theta \,{\it dz}

where E^{\#} is the solid E expressed in cylindrical coordinates. In converting from rectangular coordinates to cylindrical coordinates, the factor r is introduced into the integrand on the right.

Using spherical coordinates ( \rho ,\theta ,\phi ) , we have \iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE}f(x,y,z)\,{\it dV}=\iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE^{\#}}f(\rho \sin \phi \cos \theta ,\rho \sin \phi \sin \theta ,\rho \cos \phi )\rho ^{2}\sin \phi \,d\rho \,d\theta \,d\phi\

where E^{\#} is the solid E expressed in spherical coordinates. In this conversion, a factor of \rho ^{2}\sin \phi is introduced into the integrand on the right.

NOTE

In making a change in variables, the functions g_1 and g_2 are one-to-one.

In general, when the variables of an integral are changed, a factor, called the Jacobian, is introduced into the resulting integrand.

DEFINITION Jacobian: Two Variables

For a change of variables from x, y to u, v given by \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{ x=g_{1}(u,v)\qquad y=g_{2}(u,v) }

the Jacobian of x and y with respect to u and v is \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{ \dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} =\left\vert \begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial v} \\[9pt] \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial v} \end{array} \right\vert =\dfrac{\partial x}{\partial u}\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial v}- \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial v}\dfrac{\partial y}{\partial u} }

NEED TO REVIEW?

Determinants are discussed in Section 10.5, p. 725.

1 Find a Jacobian in Two VariablesPrinted Page 963

ORIGINS

Jacobians are named after the German mathematician Carl Gustav Jacobi (1804–1851). Jacobi was a child prodigy. By age 12, he had met the entrance requirements for university admission. He studied mathematics, Latin, and Greek and became a professor at the University of Köorionigsberg. Although he worked with functional determinants, he is most noted for his work with elliptic functions. Jacobi died of smallpox at age 46.

EXAMPLE 1Finding a Jacobian

Show that in changing from rectangular coordinates (x,y) to polar coordinates (r,\theta ), the Jacobian of x and y with respect to r and \theta is r.

Solution To change the variables from rectangular to polar coordinates, we use the equations \begin{equation*} x=r\cos \theta \qquad y=r\sin \theta \end{equation*}

The partial derivatives are \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial r}=\cos \theta \qquad \dfrac{\partial x}{ \partial \theta }=-r\sin \theta \qquad \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial r}=\sin \theta \qquad \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial \theta }=r\cos \theta

The Jacobian of x,y with respect to r,\theta is \begin{eqnarray*} \dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (r,\theta )}&=&\left\vert \begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial r} & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial \theta } \\[9pt] \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial r} & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial \theta } \end{array} \right\vert =\left\vert \begin{array}{l@{\quad}r} \cos \theta & -r\sin \theta \\[3pt] \sin \theta & r\cos \theta \end{array} \right\vert =\cos \theta \cdot r\cos \theta -\sin \theta (-r\sin \theta)\\[4pt] &=&r\cos ^{2}\theta +r\sin ^{2}\theta =r \end{eqnarray*}

NOW WORK

2 Change the Variables of a Double Integral Using a JacobianPrinted Page 964

964

In changing variables to find a double integral, we make use of the following result, which we state without proof:

THEOREM Change in the Variables in a Double Integral

Suppose R is a closed, bounded region of the xy-plane and R^{\#} is a closed, bounded region of the uv-plane, where each point in R corresponds to one and only one point in R^{\#} when the change of variables x=g_{1}(u,v), y=g_{2}(u,v) is made. If:

- f is continuous on R,

- g_{1} and g_{2} have continuous partial derivatives on R^{\#}, and

- the Jacobian \dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}\neq 0 on R^{\#},

then \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{ \displaystyle\iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR}f(x,y)\,d\!A=\displaystyle\iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR^{ \#}}f(g_{1}(u,v),g_{2}(u,v))\left\vert \dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)} \right\vert \,du\,dv }

Notice that in the integral on the right, the absolute value of the Jacobian is introduced as a factor.

Changing variables can simplify the integration of \iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR}f(x,y) \,d\!A in two ways: either by simplifying the region R or by simplifying the integrand f(x,y).

EXAMPLE 2Using a Jacobian in a Double Integral

Find \iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR}y\,d\!A, where R is the region enclosed by the lines 2x+y=0, \ \ 2x+y=3, x-y=0, and x-y=2.

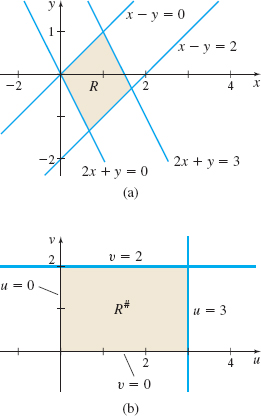

Solution We use the change of variables u=2x+y and v=x-y. Then the lines 2x+y=0 and 2x+y=3 in the xy-plane correspond to the lines u=0 and u=3 in the uv-plane. The lines x-y=0 and x-y=2 in the xy-plane correspond to the lines v=0 and v=2 in the uv-plane. As Figure 63 shows, the region R in the xy-plane is a parallelogram and the region R^{\#} in the uv-plane is a rectangle.

To find the Jacobian, we need to express x and y as functions of u and v. We can achieve this by solving the system of equations \left\{ \begin{array}{l} u=2x+y \\ v=x-y \end{array} \right. for x and y. Then x=\dfrac{u+v}{3} \qquad y=\dfrac{u-2v}{3}

The Jacobian is \begin{equation*} \dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}=\left\vert \begin{array}{c@{\quad}c} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial v}\\[3pt] \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial v} \end{array} \right\vert =\left\vert \begin{array}{l@{\quad}r} \dfrac{1}{3} & \dfrac{1}{3}\\[3pt] \dfrac{1}{3} & -\dfrac{2}{3} \end{array} \right\vert =-\dfrac{2}{9}-\dfrac{1}{9}=-\dfrac{1}{3} \end{equation*}

Using this change of variables, the integral \iint\limits_{\kern-2ptR}y\,d\!A becomes \begin{eqnarray*} \iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR}y\,d\!A &=&\displaystyle\iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR^{\#}}\dfrac{u-2v}{3}\cdot \left\vert -\dfrac{1}{3}\right\vert \,du\,dv=\int_{0}^{2}\int_{0}^{3}\dfrac{1}{9}(u-2v)\,du\,dv=\dfrac{1}{9}\int_{0}^{2}\left[ \dfrac{u^{2}}{2}-2uv\right]_{0}^{3}\,dv\\ &=&\dfrac{1}{9}\int_{0}^{2}\left( \dfrac{9}{2}-6v\right) {dv}=\dfrac{1}{9}\left[\dfrac{9v}{2}-3v^{2}\right] _{0}^{2}=\dfrac{1}{9}(9-12)=-\dfrac{1}{3} \end{eqnarray*}

NOW WORK

965

EXAMPLE 3Using a Jacobian in a Double Integral

Find \begin{equation*} \displaystyle\iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR}(x+y)\sin (x-y)\,d\!A \end{equation*}

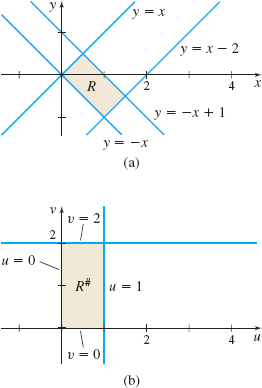

where R is the region enclosed by y=x, \ y=x-2, \ y=-x, and \ y=-x+1 .

Solution The integrand (x+y)\sin (x-y) suggests changing the variables to u=x+y and v=x-y. Then the lines x-y=0, \ x-y=2, \ x+y=0, and \ x+y=1 in the xy-plane define the region R, and the lines v=0, v=2, u=0, and u=1 in the uv-plane define the region R^{\#}. See Figure 64. We solve the system of equations \left\{ \begin{array}{l} u=x+y \\[3pt] v=x-y \end{array} \right. for x and y, and obtain \begin{equation*} x=\dfrac{u+v}{2}\qquad y=\dfrac{u-v}{2} \end{equation*}

Using these equations, the Jacobian is \begin{equation*} \dfrac{\partial (x,y)}{\partial (u,v)}=\left\vert \begin{array}{l@{\quad}r} \dfrac{1}{2} & \dfrac{1}{2} \\[9pt] \dfrac{1}{2} & -\dfrac{1}{2} \end{array} \right\vert =-\dfrac{1}{4}-\dfrac{1}{4}=-\dfrac{1}{2} \end{equation*}

The integral under this change of variables becomes \begin{eqnarray*} \iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR}(x+y)\sin (x-y)\,d\!A& =&\iint\limits_{\kern-3ptR^{\#}}u\sin v\cdot \left\vert -\dfrac{1}{2}\right\vert \,du\,dv=\dfrac{1}{2}\int_{0}^{1} \int_{0}^{2}u\sin v\,dv\,du \notag \\ & =&\dfrac{1}{2}\int_{0}^{1}\big[u(-\cos v)\big] _{0}^{2}\,du= \dfrac{1}{2}(1-\cos 2)\int_{0}^{1}u\,du \notag \\[4.5pt] & =&\dfrac{1}{4}(1-\cos 2) \end{eqnarray*}

NOW WORK

3 Change the Variables of a Triple Integral Using a JacobianPrinted Page 965

In space, the Jacobian is defined as follows.

DEFINITION Jacobian: Three Variables

For a change of variables from x, y, z to u, v, w given by \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{ x=g_{1}(u,v,w)\qquad y=g_{2}(u,v,w)\qquad z=g_{3}(u,v,w) }

the Jacobian of x, y, and z with respect to u, v, and w is given by \bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{ \dfrac{\partial (x,y,z)}{ \partial (u,v,w)}=\left\vert \begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial v} & \dfrac{ \partial x}{\partial w} \\[9pt] \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial v} & \dfrac{ \partial y}{\partial w} \\[9pt] \dfrac{\partial z}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial z}{\partial v} & \dfrac{ \partial z}{\partial w} \end{array} \right\vert }

NOW WORK

966

In changing the variables of a triple integral, we use the following result:

THEOREM Change in the Variables in a Triple Integral

Suppose E is a closed, bounded solid of xyz-space and E^{\#} is a closed, bounded solid of uvw-space, where each point in E corresponds to one and only one point in E^{\#} when the change of variables x=g_{1}(u,v,w), \ y=g_{2}(u,v,w), and z=g_{3}(u,v,w) is made. If:

- f is continuous on E,

- g_{1}, g_{2}, and g_{3} have continuous partial derivatives on E^{\#}, and

- the Jacobian \dfrac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)}\neq 0 on E^{\#}, then

\bbox[5px, border:1px solid black, #F9F7ED]{ \iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE}f(x,y,z)\,{\it dV}=\iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE^{ \#}}f(g_{1}(u,v,w),g_{2}(u,v,w),g_{3}(u,v,w))\left\vert \dfrac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)}\right\vert \,du\,dv\,dw }

Again notice that in the integral on the right, the absolute value of the Jacobian is introduced as a factor.

EXAMPLE 4Using a Jacobian in a Triple Integral

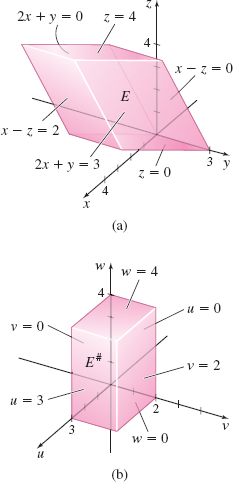

Find \iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE} y\,{\it dV}, where E is the solid enclosed by the planes 2x+y=0, 2x+y=3, x-z=0, x-z=2, z=0, and z=4.

Solution The solid E is the slanted parallelepiped shown in Figure 65(a). The change of variables u=2x+y, v=x-z, and w=z transforms E into the rectangular parallelepiped E^{\#} shown in Figure 65(b). E^{\#} is the solid enclosed by the planes u=0, u=3, v=0, v=2, and w=0, w=4.

We solve the system of equations \left\{ \begin{array}{l} u=2x+y \\ v=x-z \\ w=z \end{array} \right. for x, y, and z and obtain x=v+w \qquad y=u-2x=u-2 ( v+w ) =u-2v-2w \qquad z=w

The Jacobian is \begin{equation*} \dfrac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)}=\left\vert \begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial x}{\partial v} & \dfrac{ \partial x}{\partial w} \\[9pt] \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial y}{\partial v} & \dfrac{ \partial y}{\partial w} \\[9pt] \dfrac{\partial z}{\partial u} & \dfrac{\partial z}{\partial v} & \dfrac{ \partial z}{\partial w} \end{array} \right\vert = \left|\begin{array}{c@{\quad}c@{\quad}c} 0 & \hphantom{-}1 & \hphantom{-}1\\ 1 & -2 & -2\\ 0 & \hphantom{-}0 & \hphantom{-}1 \end{array}\right| =-1 \end{equation*}

The integral \iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE}\,y\,{\it dV} under this change of variables becomes \begin{array}{rcl} \displaystyle\iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE}~y\,{\it dV} &=&\displaystyle\iiint\limits_{\kern-3ptE^{\#}}(u-2v-2w) \left\vert \dfrac{\partial (x,y,z)}{\partial (u,v,w)}\right\vert du\, dv\, dw=\int_{0}^{4}\int_{0}^{2}\int_{0}^{3}( u-2v-2w) \,du\,dv\,dw \notag\\ &=&\displaystyle\int_{0}^{4}\int_{0}^{2}\left[ \dfrac{u^{2}}{2}-2vu-2wu\right] _{0}^{3}dv\,dw=\int_{0}^{4}\int_{0}^{2}\left( \dfrac{9}{2}-6v-6w\right) dv\, dw \notag\\ &=&\displaystyle\int_{0}^{4}\left[ \dfrac{9}{2}v-3v^{2}-6wv\right] _{0}^{2}\, dw= \int_{0}^{4}( 9-12-12w) \, dw=\int_{0}^{4}( -3-12w) \, dw \notag\\ &=&\big[ -3w-6w^{2}\big] _{0}^{4}=-12-96=-108 \end{array}