The Nineteenth Century

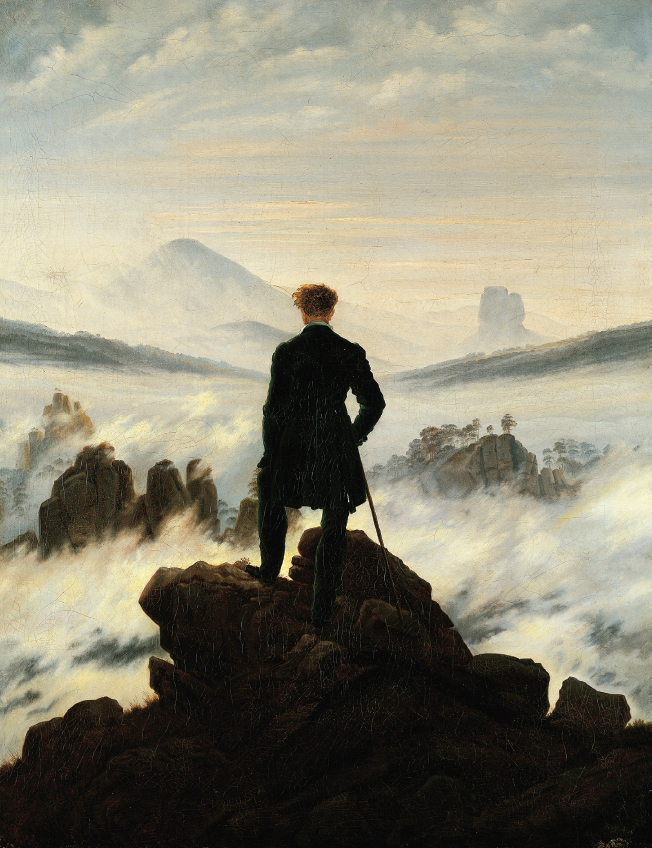

In the nineteenth century, many came to feel that music could carry them toward mysterious and awesome expressive realms—sublime realms, in the favorite word of the day. The sublime was discovered also in the natural world. In this painting by the German Caspar David Friedrich, it is rendered as a sea of fog, viewed by a lone hiker perched on a mountain crag. DEA Picture Library/De Agostini/Getty Images.

Starting with the towering figure of Beethoven in the first quarter of the nineteenth century, famous names crowd the history of music: Schubert, Schumann, Chopin, Wagner, Verdi, Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Mahler, and others. These composers created a repertory of music that stands at the heart, still today, of symphony concerts, piano recitals, and seasons at the opera house. You might be surprised to realize how many nineteenth-century tunes you recognize in a general sort of way. They tend to turn up as background music to movies and television; some of them are metamorphosed into pop tunes and advertising jingles; and many of them are available as ringtones.

Nineteenth-century music was a great success story. Only at this juncture in European history was music taken entirely seriously as an art on the highest level. Music, more than any other art, was thought to mirror inner emotional life; we tend still today to adopt this view. Composers were accorded a new, exalted role in the expression of individual feeling. They responded magnificently to this role, producing music that is more direct and unrestrained in emotional quality, and with much more pronounced personal attributes, than the music of any earlier time. The full-blooded, even exaggerated, emotion of this music seems never to lose its powerful attraction.

Like eighteenth-century music, music of the nineteenth century is not stylistically homogeneous, yet it can still be regarded as a larger historical unit. We shall take up the Romantic style, usually dated from the 1820s, after discussing the music of Beethoven. In technique Beethoven was clearly a child of the eighteenth century; but in his emotionalism, his artistic ambition, and his insistence on individuality, he was the true father of the nineteenth century. Understanding Beethoven is the key to understanding Romantic music.

| 1808 |

Beethoven, Symphony No. 5 in C Minor |

p. 209 |

| 1815 |

Schubert, “Erlkönig” |

p. 234 |

| 1820 |

Beethoven, Piano Sonata in E |

p. 216 |

| c. 1827 |

Schubert, Moment Musical No. 2 in A-flat |

p. 243 |

| 1830 |

Berlioz, Fantastic Symphony |

p. 249 |

| 1831 |

Chopin, Nocturne in F-sharp |

p. 245 |

| 1833–1835 |

R. Schumann, Carnaval |

p. 244 |

| 1840 |

R. Schumann, Dichterliebe |

p. 238 |

| 1843 |

C. Schumann, “Der Mond kommt still gegangen” |

p. 241 |

| 1851 |

Verdi, Rigoletto |

p. 259 |

| 1851–1856 |

Wagner, The Valkyrie |

p. 269 |

| 1869–1880 |

Tchaikovsky, Overture-Fantasy, Romeo and Juliet |

p. 279 |

| 1874 |

Musorgsky, Pictures at an Exhibition |

p. 284 |

| 1878 |

Brahms, Violin Concerto in D |

p. 289 |

| 1888 |

Mahler, Symphony No. 1 |

p. 293 |

| 1904 |

Puccini, Madame Butterfly |

p. 275 |